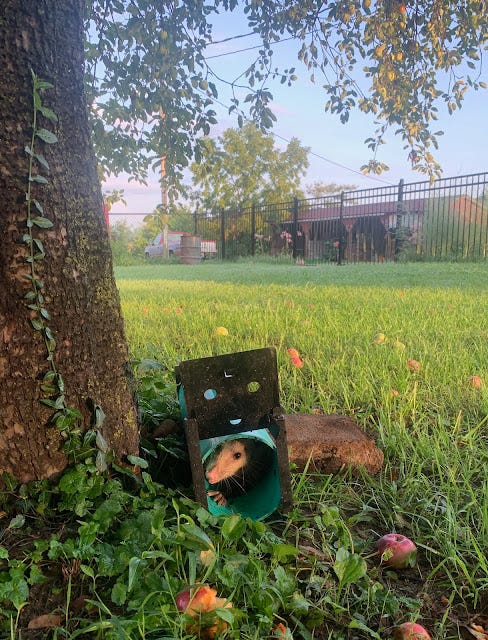

not a groundhog

The young man my father hired to help out with chores he can no longer handle is setting out to mow. He steers our large mower towards the barn lot, his posture relaxed but his rifle at the ready, resting long across his lap. We have acquired our own sharpshooter. Since he shares a name with my own husband, we call him Young Garrett. (My Garret I only call just that – “My Garret” – not wanting (yet at least) to style him “Old.”) Young Garrett is a prize-winning trap shooter and, at but seventeen, a startlingly accomplished naturalist. We have set him armed upon the place in hopes that he can aid with our late trouble. We are under siege by groundhogs.

For a peaceful decade, we had hosted at least one groundhog, as evidenced by the longstanding hole just under the wall of the milk barn. But about four years ago, we noticed holes beginning to appear inside the old calf barn and underneath the shop. None of this was good or acceptable – groundhogs can be quite destructive – yet it likewise seemed a kind of tolerable, the sort of problem one puts off and off, postponed for an imagined sometime coming day when nothing else wants one’s attention more. But what began at slow and steady pace has found a sudden increase. We have holes now in the dozens, groundhogs in a number I hesitate to guess. So overrun has our area become that even our gentle, vegan neighbor confessed she wanted to buy a gun and learn to shoot. It was then that I belatedly faced up to our trouble and set myself to fix it.

I am not a natural at the bits of farming that set one at war with other creatures. I prefer to co-exist whenever we can manage it. All the same, one doesn’t get to live that way – not when, say, mating skunks take up residence under the bedroom or pack rats try to winter over under the hood of our best truck. Even so, I try to keep my heart tender. I have a skunk trap that will sometimes work. It’s designed to lure the creature into a long tube, there to hold it where its noxious tail can’t raise. What happens next is a matter of some ambiguity, a choice left to the trapper. I don’t drown them as some would, but instead take them to church. If you will relocate a skunk, you need to take it far, too far to make its way in some return. So that is what I do. There is a native stone church some nine miles down our dirt road, the church long ago abandoned and left empty. It’s nestled up a hill by woods that I would like were I a skunk. So I take my skunks there. (It helps to have a building I can hide behind when time comes to open up and release them – the drive to church does tend to make them irritable.) Like the skunks, the groundhogs cannot be left to live with us, lest the hordes now upon us really do undermine a barn or have us breaking axles or ankles across their many holes.

My efforts in groundhog control began in modest ways. Groundhogs do not like foul smells, and so stinking up their territories seemed a good first step to take. Coyote urine was far too costly, so I settled on vinegar for my stink, bathing the holes under a barn daily. But it turns out that if you will stink up a groundhog’s hole, she’ll just dig another entrance to her tunnel. So I put my vinegar away and started setting out a trap.

My groundhog trap is a humane sort, a welded wire cage that closes behind a creature once it steps on a metal plate to retrieve the bait. For days, I set that trap with cantaloupe and waited, all to no avail. Our finest apple tree was then producing and I speculate that the groundhogs had no need of storebought melon when we had a grassy patch of glorious windfall regularly on offer. This is not to say that the trap failed entirely to work, for work and overtime it did. Within two weeks I had caught three possums, one armadillo, and five raccoons. The possums I would just release, for they eat ticks and we really like them for it. I took the armadillo off to our far woods, hoping he would not come back, but by then not caring overmuch about a one such as himself. Because they are so crafty and so diabolical, the raccoons I took out to that church. They arrived in my traps in such quick succession that I began to tire of the long drive each would require. I consoled myself with speculative imaginings about their later fates. I fancied them out there forming a new religion, one that has as origin myth a Great Relocation. Raccoons only travel by their feet, but these would with their feet confined still end up somewhere new – surely a fate most radical and peculiar, if one is a raccoon. Each alone might think he was gone slightly mad, but together, their common story of the Relocation would start to seem like more. It could be a tale to circulate for generations about how they started out in one place and then – somehow, no one can say for sure – they ended up in another, all together and at church. Such is the stuff of which myths could readily be made. But none of this was consolation for my elusive groundhogs.

As is the way with much out here upon our farm, one sometimes has to give up searching in the predictable places for solutions. What the internet or extension office can’t tell you, someone out here might. So I started talking of our groundhogs whenever circumstance gave me the chance. This is how I began to assemble a catalog of ways to get rid of groundhogs.

The most straightforward way to rid oneself of groundhogs is to kill them and the most straightforward way to kill a groundhog is naturally to shoot it, but unless one will live armed, it is a solution not well matched to circumstance. One needs a gun just when chance puts a hog across your path and since I wasn’t going to carry constantly, this was not a remedy to work. Since all around are alert to just this trouble, most of the local solutions involve strategies for getting groundhogs to appear. One neighbor suggested strings of Black Cats, those percussive small fireworks that in clusters can make quite a chaos. Just light and toss those in the hole, he said, and wait there with my gun: When the noise sends the groundhogs out, have your rifle at the ready. Even if I could reconcile myself to this, it didn’t seem for me too prudent. I am not a graceful person, a deficit a loaded gun could only complicate. So, too, I recalled my grandfather’s talk of “some old fella” who tried to shoot an armadillo and instead shot his own trailer. The bullet ricocheted from there to hit his dog right in the eye. I too much like my dog and his fine eyes to try to aim my rifle amidst a haze of fireworks.

One of my father’s friends offered up flooding as a better solution than a gun can do. Block up any exits, then just run the hose down in a hole and let the water rip till naught inside could well survive. This had its appeal, but still, I foresaw problems. While my hose is long, the groundhogs don’t take care to only dig within its reach. The holes my hose can get are also those beneath our barns and I don’t trust our now aged structures to withstand flooding underneath. I could well conceive a watery grave full of groundhogs and a sunken barn atop. Similar reservations had me balking at what a guy down at the feedstore promised worked a trick. He, too, suggested fluid down the hole, but gas instead of water. “Just run some fuel down in those holes,” he said with energy that made me uneasy, “then light ‘em up!” Having rejected the elements of both water and fire, air presented as another possibility when another feed store fellow suggested I gas the creatures out: Connect a hose from the exhaust of the truck down into a hole and run the engine till a toxic excess of emissions poisons any groundhogs luckless enough to be at home. Here, too, a little gunfire might be joined with fumes, as I could shoot any coughing hogs that emerge to flee a death by poisoned air. I had no ready, clear objection to this approach – no sense that with it I might destroy more than I meant. Yet still I could not like it, and disliked it with an unsettling but utter certainty that I would never try it. This failure to find a strategy that I could bear or trust is how we came to hire our young gunslinger.

Young Garrett is the best shot for miles around, but even he is struggling. He has succeeded where I did not, his tally of groundhogs killed now at three. He is always armed, but on the whole, his efforts so far have proven much like mine, with lots of accidental catches in the mix, though his catches meet an end far grimmer than mine did. After one especially noisy afternoon of gunfire coming from the barn lot, Young Garrett came in to report that while he added no more hogs to his existing tally, he had managed still to shoot one snake, one snapping turtle, and two mice. (He is indeed a good enough shot to hit a mouse.) That day, he came in talking like I used to do, speculating about the use of water or of firecrackers. I know he has at least once built a small fire at a hole, aiming to smoke them out from under ground and put them in his ready sights. Yet still they largely have eluded him. Some days, in frustration, he consoles himself with shooting walnuts from the walnut trees. My real hope is that Young Garrett will succeed most in the cacophony he raises, in making ours a place of such menace that the groundhogs will in prudence simply leave. It hasn’t happened yet.

While we remain obliged to live alongside our destructive diggers, I seek what comforts I can find. I school myself in ways that groundhogs might be counted good. By now I know all the benefits they bring, though I count these spare and inadequate to my own purposes.

Groundhogs are of course most famous for their purported predictive powers, for their emergence on Groundhog Day to let us all know what we may expect of coming weather. This seems a talent, to be sure, but not one we especially need round here – as if a farm place utterly overrun by weathermen who work one day a year could justify the destruction that they otherwise create. But groundhogs can do more than this. All that digging can be useful to the soil. Turned and aerated earth is healthier all round, preventing compacting and giving roots a chance to thrive. Still, the places ours have chosen most to dig are free of trees whose growth we would encourage, nor do the mounds of graveled earth they leave outside each hole well testify to any aid they might be offering. So rocky is our soil that they mostly turn up fresh stone to foul a mower blade.

Of the benefits that groundhogs give, the greatest by far are not for us, but for others of their kind. It turns out that they are generous souls and even as they seem to want to crowd us out, they’ll play host to others who like to den up in the colder months. They let other creatures come on in, sharing their tunnels with voles and chipmunks, even foxes or, to their own detriment, coyotes. I want to find in this a good that I can prize, but wanting to think something good and really thinking it good are not the same.

The good that groundhogs give are benefits for the big of mind, for those willing and able to think of thriving in totalities. I do not want mine a land of deadened soil, nor yet would I wish mine a place where voles and chipmunks are denied warm rest in winter. I likewise understand that we, my people on this place, are but a small part of its population. Most things out here have some part to play in the elaborate overall, and it is a fool who sacrifices to human preference some bit of nature necessary to the whole. We live with traces of ill-begotten efforts to contain and manage this or that. The invasive multiflora rose against which we make ongoing war was brought in deliberately. What was thought to be good planting against erosion has now become but utter aggravation, a pretty misery that crowds out what once belonged and freely grew here. In short, small-minded mistakes already pepper the landscape for those who know its history. I do not want to be small-minded, nor to solve a problem just to make another that is worse. Yet still, I struggle. While I realize intellectually that what profits fox or vole can also profit me, I cannot make this a truth by which to live.

I started out writing all this business about our late groundhog troubles with a purpose, but as with most my efforts, I have now drifted. Because I am supposed to be writing a book on grief and sorrow but cannot seem to write it, I inhabit the fact of this as if it is a prison. I haunt the cell of “philosophy of loss,” poking round the walls and hoping for a yielding door – which is to say that I am ever on the hunt for some way out of mute frustration and into the writing of this thing I’m meant to write. Perhaps if one will try to write a book on loss and the sorrows that it brings, one will come to see too much in the register of those resistant struggles. This, at least, is how it is for me and for all this business with the groundhogs.

All those philosophers writing up their thoughts about death and what it means strike me as just so many fellows at the feed store. They all have their ideas about what might make the trouble yield and they’re all probably right sometimes, but only sometimes. The best of them are sharpshooters, but even those can most days only miss. I’m sure a little Stoicism might help a bit when you want to fall apart, just as surely as smoking them out might kill a groundhog or two. But it’s all just stuff to try and it’s all got an underlying air of foolishness about it, an atmosphere of desperation and a whiff of inept futility. If you’re foolish enough to treat any one of all this stuff as a definitive solution, you can transform an ordinary trouble into disaster, burn the barn down or collapse it in a heap. Still, I thought, maybe the way into writing about grief and loss is just to own up to the fact that no one yet has worked this stuff truly out – really, that this stuff can never truly be worked out. The best you’re ever going to get is a catalog of possibilities, none reliable and all in some way vexed. You can reach here to water, there to gasoline, another day to fumes. And throughout your labors and your trouble, you’ll struggle still to take that wider view – the view that death, like groundhogs, has some helpful place in the overall. That elusive wider view of things won’t save your ankle if you stumble in a hole, but it might console you some against the pain. It is all about the might, and never about what really works because nothing really does.

These were my thoughts in writing about groundhogs. See, the groundhogs were just an analogy, a way to frame what I could say of grief. But I won’t really write of grief that way, or maybe any way at all. Each time I push against the door of this, my prison, it takes me somewhere else. Today it was to groundhogs and their several holes upon our place, of the mazes lying hidden beneath the surface of the seen. My words are like Young Garrett’s shot. I pepper the page with verbal buckshot, but keep bringing back things that never were meant to be my target. I cannot kill grief, so I just harass it with my misplaced, noisy words.

also not a groundhog

maybe a way to write an unwritable book is to write around it